Why are most firms are having such problems with their digital transformations? While many have realized that their future lies in digital, most have yet to grasp that a digital transformation requires deeper change than merely computerizing industrial era processes. The reality is that industrial-era management and digital-era leadership are two different worlds.

The world of industrial-era management is vertical. Its natural habitat comprises tall buildings in big cities. Its mindset is also vertical. “Strategy gets set at the top,” as Gary Hamel often explains. “Power trickles down. Big leaders appoint little leaders. Individuals compete for promotion. Compensation correlates with rank. Tasks are assigned. Managers assess performance. Rules tightly circumscribe discretion.” The purpose of this vertical world is self-evident: to make money for the shareholders, including the top executives. Its communications are top-down. Its values are efficiency and predictability. The key to succeeding in this world is tight control. Its dynamic is conservative: to preserve the gains of the past. Its workforce is dispirited. It has a hard time with innovation. Its companies are being systemically disrupted. Its economy—the industrial-era Economy—is in decline.

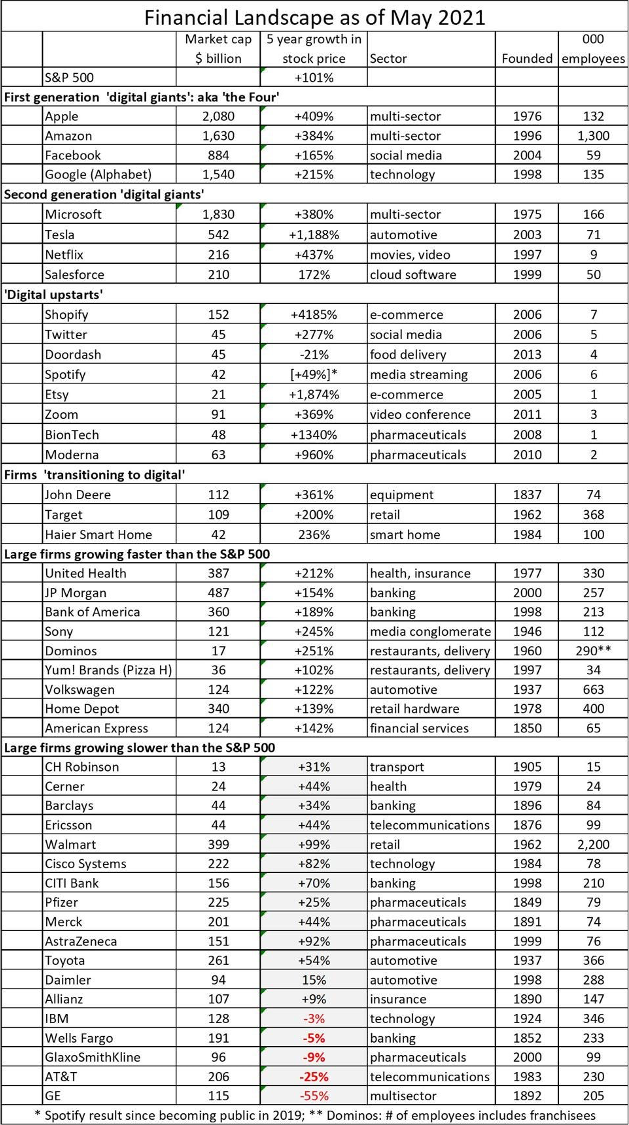

The world of the digital age is horizontal. Its natural habitat is in low flat buildings in places like California, although it also spreading rapidly like a virus and has already established footholds in most of the tall vertical organizations. It’s not just the buildings: it’s the digital mindset that is also is horizontal. Its purpose is to delight customers. Making money is the result, not the goal of its activities. Its focus is on continuous innovation. Its dynamic is enablement, rather than control. Its communications tend to be horizontal conversations. It aspires to liberate the full talents and capacities of those doing the work. It is oriented to understanding and creating the future. It believes in banking, not necessarily banks. It believes in accommodation, not necessarily hotels. It believes in transport, not necessarily cars. It believes in health, not necessarily hospitals. It believes in education, not necessarily schools. Its economy—the digital economy—is thriving and crushing the world of industrial-era firms, as shown in Figure 2.

Industrial-era management practices took many years to evolve and are now ingrained as a way of life in industrial-era corporations. Many senior executives have grown up and made their careers in corporations run on that basis. They often owe their position to their success in operating in this vertical world. They are rarely familiar with, or comfortable in, the horizontal world of the digital-era leadership. They frequently delegate to the digital transformation to some another executive in the upper middle part of the organization, while they get on with “the real business of running the company”—in the industrial era manner. Their boards are often equally ill-equipped to deal with the digital era and often encourage the C-suite to keep doing what they too are familiar with.

Meanwhile the financial sector has come to expect little innovation from these industrial-era behemoths, and focuses most of its attention on extracting value from the industrial-era firms while placing its main bets on digital, as shown in Figure 2.

So top level decision-making and thinking in industrial era firms tends to continue in the vertical mold, where the collaboration across boundaries required for digital leadership is unnatural. It’s no real surprise then to find that most efforts are digital transformation are currently failing.

The reality is that age-old practices can’t shifted overnight. Even with strenuous leadership from the very top, many years of work will be needed for an industrial-era firm to shift its principles and processes to those of digital-era. When the heart of leadership at the very top isn’t in the transition, it’s uncertain whether the change will ever take.

Meanwhile vertical world of industrial-era management likes to defend itself as “the adults in the room.” An interview with Sam Palmisano, former CEO of IBM, in June 2014 in HBR is typical:

"You’ve got companies in great runs right now, the Googles and the Facebooks. Good ideas, great returns, but then all of a sudden, you need an act two. Well, jeez, is act two going to propel you from $30 billion to $100 billion? That’s a little tougher. It’s the Microsoft challenge.”

"So you have to say, 'Well, I need a different view. I can still create shareholder value, but I can do it a different way. I can rethink capital allocation.' Recognize where you are on your maturity curve, as a management team, and behave accordingly. Don’t give a speech as CEO as if you just got out of Stanford and you came up with an iconic interface and you called yourself a piece of fruit.

Sadly, the real world, even in 2014, was the opposite of the imaginary world that Palmisano inhabited. The firms with “names like pieces of fruit” were not “$30 billion firms,” even in 2014: Apple was already more than four times the size of IBM. Now it’s twenty times.

And “the Microsoft challenge”? Microsoft is one of the few industrial era behemoths that has made the transition, as I have explained here and here.

Whereas formerly-market-leading firms like IBM are struggling with declining revenues and bloody cost-cutting reorganizations, firms in the horizontal world of Agile, like Apple, Amazon, Microsoft and Google are trillion-dollar firms, busily growing and inventing the future. Their second, third, and fourth acts are already under way. As figure 2 shows, unless industrial-era firms can find the courage and the smarts to make the transition to the digital-era with a different kind of leadership, they will soon be history.

Steve Denning

Steve Denning is the author of six successful business books on leadership, leadership storytelling, and management, as well as a novel and a volume of poems. Since 2011, he has been writing a popular Leadership column for Forbes.com and has published more than 600 articles on the Creative Economy, with more than 6 million visitors and more than 15 million page views. He has interviewed eminent gurus such as Clayton Christensen.

Steve is a member of the Advisory Board of the Drucker Forum, headquartered in Vienna, Austria. The annual Drucker Forum, held in November each year, has become the leading global conference on general management issues. Each year, Steve has chaired a panel at the Forum, which attracts the world’s top thought leaders in management.

Steve Denning is the author of The Age of Agile, The Leader’s Guide to Radical Management: Re-inventing the Workplace for the 21st Century (Jossey-Bass, 2010), The Secret Language of Leadership (Jossey-Bass, 2007) and The Leader’s Guide to Storytelling (Jossey-Bass, 2005).

From 1996 to 2000, Steve was the Program Director, Knowledge Management at the World Bank where he spearheaded the organizational knowledge sharing program.